The hit TV series “24” always got my attention. Yes, I am a sucker for shows about spies, undercover cops and counter-terrorists. But in addition to all of the shoot-em-up theatrics, I could always count on that show to exploit the innate tension between two classically different approaches to ethics.

Utilitarians determine the moral quality of an act based on the ends that act is likely to produce. If the benefits outweigh the harms, the act is justified. Deontologists, in contrast, believe the moral quality of the act is inherent in the act itself, separate from the ends it produces. (There are lots of variations on these themes, and there are other ethical schools, but these two camps cover a lot of the philosophical landscape of ethics.)

The setting for the TV show is rich for pitting these two ethical approaches against each other. Is torture inherently wrong? What if it could possibly save the lives of millions of others? The show’s writers have Jack teetering constantly between the arithmetic of utilitarianism and the duty inherent to deontology.

But one thing the writers didn’t anticipate is that how Jack makes these decisions might depend on whether he was thinking about them in another language. Spanish researchers asked bi-lingual subjects to make an emotionally charged, ethically challenging decision. For some subjects, the ethical problem was written in their native tongue; for others it was in the other language they spoke.

What they found is fascinating: the fraction of subjects who took a utilitarian view rose dramatically (from 20% to 33%) when the decision was written in the foreign language instead of their native tongue. And the effect was even greater for subjects who weren’t as proficient in that foreign tongue (i.e., had to work harder mentally to understand the problem).

The study suggests that slowing people down – in this case, by presenting the problem in a different language – causes them to engage a less emotional and more objective decision-making strategy. This is another case of how fluency (or in this case, disfluency) can advantage some choices over others. As such, it’s an application of the fifty bits über lever of simplifying wisely.

A NOTE ABOUT THE STUDY

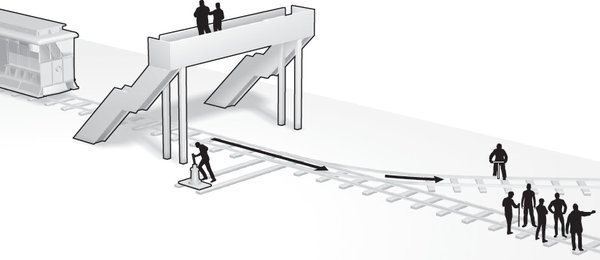

The ethically challenging decision used by the researchers is known as “the trolley problem.”

Here’s how the researchers describe the problem:

We used the “footbridge” version of the trolley dilemma, where one imagines standing on a footbridge overlooking a train track. A small on-coming train is about to kill five people and the only way to stop it is to push a heavy man off the footbridge in front of the train. This will kill him, but save the five people. A utilitarian analysis dictates sacrificing one to save five; but this would violate the moral prohibition against killing, and imagining physically pushing the man is emotionally difficult and therefore people routinely avoid that.

There’s slight variation on the trolley problem that involves pulling a switch to change which track the trolley is headed down. Pulling the switch saves five people on one track but sacrificing another person on a different track.

Interestingly, the language effect completely disappeared when this version of the problem was used.